Why single-dose doxycycline after a tick bite is bad medicine

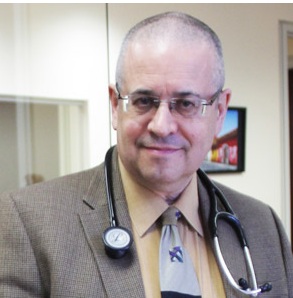

By Dr. Daniel Cameron

What if you did everything right after a tick bite—and still ended up sick?

That’s what happened to a 37-year-old woman who followed medical advice after a hike in New York’s Hudson Valley. She removed an engorged tick and went to urgent care. The provider gave her a single pill—200 mg of doxycycline—and told her it would prevent Lyme disease.

Weeks later, she developed brain fog, crushing fatigue, and joint pain. It turned out she did have Lyme disease, and possibly other tick-borne infections too.

Her case raises important ethical questions: Are patients being told enough? Are they being protected—or falsely reassured? And are we doing right by those who follow the rules?

The promise of a single pill after a tick bite

The CDC currently recommends a single dose of doxycycline after a tick bite in certain cases. The idea is simple: take the antibiotic early, and you might prevent Lyme disease from taking hold.

But there’s a catch: this one-pill approach was based on a small study published in 2001. It mostly looked at preventing the bull’s-eye rash—not the full illness.

What’s more, the study didn’t follow people long enough to detect cases of Lyme disease that develop without a rash, or cases involving co-infections like Babesia.

What this patient wasn’t told

This woman wasn’t warned about the limits of the single-dose strategy. She wasn’t told that:

It may not prevent the whole disease—just the rash.

It doesn’t protect against other infections ticks can carry.

It only works in very specific situations (right kind of tick, right timing, right area).

If symptoms appear later, Lyme disease testing can be unreliable.

Because she believed she was protected, she waited too long to seek further care—and her test came back negative at first, adding to the confusion.

By the time she arrived at my clinic, her illness had worsened.

Why This Isn’t Just a Medical Issue—It’s an Ethical One

1. Patients Deserve Full Information (Autonomy)

She should’ve been told that the one-pill approach isn’t a guarantee. Without all the facts, she couldn’t make a truly informed choice.

2. Care Should Be Tailored, Not Just Protocol (Beneficence)

She lived in a high-risk Lyme area. The tick was attached long enough to transmit disease. She might have benefited more from a longer antibiotic course. Instead, a “one-size-fits-all” approach failed her.

3. False Reassurance Can Do Harm (Non-Maleficence)

Believing she was safe delayed her diagnosis and treatment. That delay caused more suffering—and made recovery harder.

4. The System Isn’t Fair for Everyone (Justice)

This strategy doesn’t work well for kids under 8, pregnant women, or people who don’t have easy access to care. It assumes everyone knows what kind of tick bit them—and can get treatment within 72 hours. That’s not realistic for many.

What happened when she got the right help

When she finally got to my office, we ran new tests. Her Lyme Western blot confirmed infection. She also had symptoms of Babesia, a parasite that doxycycline doesn’t treat. On top of that, she had orthostatic intolerance (POTS), which had never been linked to her tick bite before.

With a more complete treatment plan—including antibiotics and supportive care—she began to feel better. But the road was longer than it needed to be.

Bottom line: A simple solution isn’t always the right one

The idea of “just one pill” sounds great—but it can create a false sense of safety. When patients aren’t told the full story, they lose the chance to make informed decisions. And when symptoms are dismissed, the consequences can last for months or even years.

We need to do better. That means:

- Being honest about what the single-dose approach can and can’t do.

- Offering follow-up when patients remain unwell.

- Considering co-infections and other risks—not just following a checklist.

Because when it comes to Lyme disease, patients deserve more than a protocol. They deserve a plan.

Dr. Daniel Cameron is a nationally recognized expert in the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. He is a past president of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society and a co-aauthor of the ILADS Lyme treatment guidelines. This blog first appeared on his website, danielcameronmd.com. He can also be found on Facebook.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page