- Home

- Find A Physician

- FIND A PHYSICIAN

- LymeTimes

- Current Issue

- Archives

- FEATURED LYMEDISEASE.ORG ISSUES

- Resources

- LYME LITERATE PHYSICIAN VIDEOS

- Physicians

- Members

- About Us

- Resources

O n April 27, 2020, the rubber hit the road for the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG). What seemed like a routine vote quite unexpectedly turned out to be highly significant—because of what it showed us about many members of the Working Group.

This clarifying moment materialized around the issue of persistent Lyme disease, always a controversial issue in the medical world.

But first, some background.

The TBDWG is a federal panel under the auspices of the US Department of Health and Human Services. Over the past year, it has held meetings, received and voted on recommendations from its various subcommittees, and started the process of compiling a report to Congress that is due in November 2020.

In March, the panel dealt with most subcommittee recommendations during two days of in-person meetings in Philadelphia.

A few remaining issues filled the agenda of the April 27 online meeting. These included recommendations from the Federal Inventory Subcommittee. (Sounds eye-glazing, I know. Who knew we were in for such a show of fireworks?)

The TBDWG had previously asked pertinent federal agencies to provide an inventory of any programs that relate to tick-borne diseases. The goal was to figure out what’s already happening and what still needs to happen.

Based on this research, this subcommittee offered several recommendations that sailed through without a problem. Then things hit a snag with the following proposal:

Recommend that IF the CDC posts any Lyme treatment guidelines, that they include guidelines on persistent Lyme disease.

CDC provides nothing about persistent Lyme disease

It is important to know that the CDC website currently only provides information about early Lyme disease. It offers nothing for people with persistent Lyme, those still sick and suffering long after the acute phase has passed. Non-recognition of persistent infection is a central concern of the Lyme disease community. It is why we fought to have the TBDWG formed in the first place, and why we’ve continued to fight for adequate representation of chronic Lyme patients. (The first incarnation of the Working Group, which prepared the 2018 Report to Congress, had three representatives of the Lyme patient community. This panel has only one, the Lyme Disease Association’s Pat Smith.)

It’s also important to know that for many years, the CDC openly endorsed the IDSA’s Lyme treatment guidelines—which do not acknowledge persistent Lyme. Currently, while the CDC does not list any Lyme guidelines on its website, the Lyme information it posts is consistent with the IDSA guidelines. Thus, to recommend that the CDC include guidelines about persistent Lyme was a big deal—one sure to draw a strong reaction.

As I listened to the online meeting via my computer, I couldn’t always tell who was speaking—or even, sometimes, what they said. Here’s what happened next, as near as I could tell:

Vote on recommendation regarding persistent Lyme disease

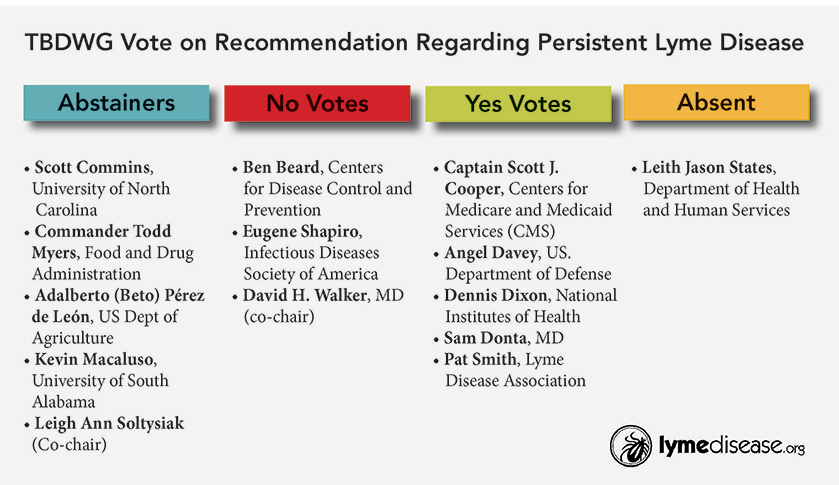

The recommendation regarding persistent Lyme disease was moved and seconded. Then, for unstated reasons, five panel members abstained from voting. The vote was announced as five abstaining, five yes votes and three no votes.

Remarks made after the vote made it clear that the abstainers felt they had defeated the measure, because “yes” votes didn’t comprise a majority of panel members. But, OOPS, guess what? Abstentions don’t count one way or the other. So, the recommendation passed, 5-3.

As that reality sank in, pandemonium broke out. Panelist Scott Commins stoutly announced that he wanted to change his abstaining vote to “no.” He was told that Robert’s Rules of Order doesn’t allow you to change your vote after the fact.

Things then got very bizarre very fast, with many people talking at once. Some wanted to vote on the original question again. Others didn’t. Some wanted to re-open discussion, others didn’t. It was very confusing to the listener at home.

However, the five abstainers sure gave the impression they had been trying to game the system—to gain a “no” vote without having to publicly own up to it. When that ploy didn’t work, they scrambled to recoup their original objective— to deep-six the proposal regarding persistent Lyme disease.

Concerted effort to minimize Lyme disease

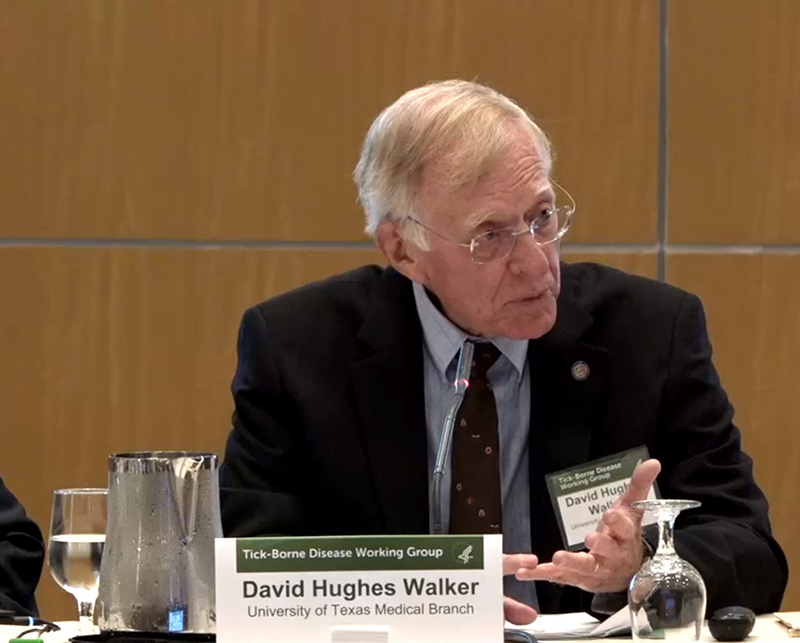

That’s what this whole kabuki dance has been about since the inception of this 2019-2020 panel of the Working Group. There’s been a concerted effort to minimize Lyme disease as much as possible. It started by choosing only one representative of the Lyme community to serve on the panel. Then, at its first meeting, Co-chair Walker announced that the previous panel had spent enough time on Lyme disease, and he didn’t want the group to devote any more time on it. And it’s why, even though Lyme disease makes up 80% of the cases of tick-borne disease in this country, it will get only 25% of the TBDWG’s upcoming report. (Two chapters out of eight.)

That’s what this whole kabuki dance has been about since the inception of this 2019-2020 panel of the Working Group. There’s been a concerted effort to minimize Lyme disease as much as possible. It started by choosing only one representative of the Lyme community to serve on the panel. Then, at its first meeting, Co-chair Walker announced that the previous panel had spent enough time on Lyme disease, and he didn’t want the group to devote any more time on it. And it’s why, even though Lyme disease makes up 80% of the cases of tick-borne disease in this country, it will get only 25% of the TBDWG’s upcoming report. (Two chapters out of eight.)

However, despite the strenuous complaints of the “anti-persistent Lyme camp,” ultimately, there was no re-discussion nor re-vote on this original recommendation:

Recommend that IF the CDC posts any Lyme treatment guidelines, that they include guidelines on persistent Lyme disease.

For now, the motion stands. But the flash of true colors displayed in this episode clarifies who is and who is not working in our best interests. This panel will disband after its November 2020 Report to Congress. But there will be a third panel of the Working Group, serving from 2021-2022. Meaningful representation of the Lyme patient community is crucially important. Without it, we’ll be stymied in our efforts to bring about the change we need.

Editor’s note: Any medical information included is based on a personal experience. For questions or concerns regarding health, please consult a doctor or medical professional.